ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Here’s a headline. Bremont has a new manufacture movement, all of its very own. Finally.

This evening, the British watch company will introduce ENG300 to the world, a 65-hour automatic with a silicon escapement that’s heavy with components manufactured at “The Wing,” the brand’s newly opened watchmaking facility. Would that that were the sum of it. But it’s not.

Which is why I hope you’ll forgive me the indulgence of saying that this has been one of the most challenging watch-related stories I’ve ever had to write. There are two reasons for this.

First is that covering Bremont’s newly minted movement is, for a British watch journalist, potentially hazardous. I’ve known the brand and many of its people, particularly its founders Nick and Giles English, for almost 15 years. We were all a lot younger and a lot less experienced back then than we are now, and we’ve done a lot of our growing up together, at least in the professional sense. I can’t say I’m as dispassionate about this new movement story as I would be about the equivalent from another, perhaps even any other watch brand. Frankly, I’d be delighted if ENG300 were a box-office smash.

If that’s some sort of up-front disclosure, perhaps I should add some context, too. I spent six hours at the Bremont Manufacturing and Technology Centre – “The Wing” – two weeks ago and spoke with Nick, Bremont’s MD Chris Reynolds, and a number of the company’s senior engineers. Among them was Head of Technical, Michael Bellamy, whose 30-year CV includes setting up 54 watchmaking workshops, and seasons with Rolex, Richemont, and Audemars Piguet, where he qualified to work on the brand’s perpetual calendars. I also spent an hour on Zoom with Bremont’s new partner last week – but let’s not spoil it by saying who that is just yet or why they matter (a lot). We’ll come to that.

Bremont’s top brass are, it must be said, somewhat nervous about how ENG300 will be received. They’ve been burned before (about which not much more needs to be said, but we’ll come to that, too) and implored me not to haul them over the coals in this story. While they were extraordinarily open and shared far more than any brand has ever shared with me before about how they made a movement, there were also things I saw and heard they asked me not to share – some of it IP, some of it stuff they want to keep their powder dry on. Out of respect and, yes, some sense of self-preservation, I’ve honoured that. And, of course, they’ve not seen this story before it lands, and, even allowing for my discretion, it’s highly likely that when they do, I’ll get a phone call. That’s ok, I’ll be fine – and thank you for your concern.

The second is simply that it’s a complicated tale with a plot line that centers around the twisted business of actually building new watch movements. Mechanical watchmaking may be a 300-year-old game, but it’s still bloody hard.

To the story of Bremont’s ENG300, then.

It’s not the story we were expecting. Let’s begin it five, maybe six years ago. Truth is, I can’t remember the first time I heard Bremont say that it was developing a movement. It's said it so many times since, each time building the anticipation, that it’s become a fixed part of the brand’s narrative. Facilities have been opened and closed, machines bought and sold, countless watches launched, but until now, there has been no sign of the elusive, British-made, Bremont-owned movement.

Stephen McDonnell, the Irish watchmaker and movement designer who was once a senior instructor at Switzerland’s prestigious Wostep watchmaking school and who has worked with MB&F and Christophe Claret, was announced as the movement’s designer, and the ambition appeared to be to create a contemporary tractor movement that could be industrially produced in Britain, and in such a way that Bremont could claim it as its own.

As the years passed, it became clear Bremont was finding that building a movement from the ground up was easier said than done, even with McDonnell’s expertise in the locker. The Swiss would have known this. Their factory floors are littered with failed attempts to build mechanical movements. But they’re not always much for sharing …

Bremont did not know this. Or, if they did, perhaps they didn’t want to hear it. Enthusiasm and wide-eyed ambition have that effect. During my visit, Nick English admitted for the first time that the McDonnell movement is simply too damned complicated to be industrialised on the scale and at the price point they’re targeting. It happens.

That, since we’re here, does not mean it won’t ever see the light of day. Bremont says it’s still a work in progress, and that when it comes, it will be produced in very low volumes and cased in high-end, high-tariff watches. The experience of ENG300 will help. Whether there’s a Bremont watch and a Bremont customer for it are questions for another day.

ADVERTISEMENT

Outside Influence

There’s only so much good money you can pour after bad. And there’s only so long you can string people along, before they think you’re bluffing – or that you’ve failed. Two-and-a-half years ago, Bremont appointed engineering logistics expert Chris Reynolds as managing director. Reynolds had come from the rather less romantic world of electric motors, working as operations director at Parvalux, and brought with him not just the ability to organize a manufacturing facility, but some much-needed pragmatism.

Under his leadership and through an industry contact Bremont is keeping under wraps, the company entered into a conversation with THE+, a Bienne-based independent formally established in 2019, but which was founded by the same team behind Momo+ and the largely unknown dial name, Horage. Together, these companies are part of a disruptive, entrepreneurial generation of Swiss industrial movement creators and manufacturers set up in response to Swatch Group’s announcement in 2003 that it would stop supplying its industry competitors with ETA movements.

Photo: The Naked Watchmaker

THE+ and its sister companies had spent seven years developing an automatic calibre it called K1. To that point, this modular, contemporary, not unattractive calibre had only appeared in an Horage watch. Today, Horage retails K1-powered watches from $2,260, and its KT tourbillon in pieces from under $7,000. Real-world value, which it defines as a counter to the hyper-inflated prices of its competitors, is one of its tenets. The base K1 movement had a silicon escapement and a 65-hour power reserve, and could be configured in 18 different ways to carry low-level complications such as a small seconds, a big date, and a power reserve.

This, Bremont decided, was the shortcut it needed. It bought the rights to use the K1 IP and upgrade it, although not exclusively (and for an undisclosed sum). THE+, which is the partner I spoke to last week, says it would sell the IP to other brands, but that it really only wants to do so if brands are prepared to acquire the manufacturing IP, too. Bremont, it says, is the only company to take on the challenge so far and develop a manufacturing program, rather than simply buying assembled movements, parts, or even drawings. It doesn’t expect many more to follow, such are the risks.

Led by Bellamy and his colleagues Martin Pennock (head of product development) and Stuart Anderson (applications engineer), Bremont then added elements that would make K1 more robust and more accurate, including an extra movement clamp, a double-footed escapement bridge, and a screwed balance wheel.

Nick et al are keen to press home this latter development, which elevates ENG300’s architecture well above that of ETA’s workhorse automatics. Publicly, they’ll say accuracy is to within chronometer tolerances of -4/+6 seconds a day, but unofficially, they’re confident of a highly respectable +/-3 seconds a day, only a second outside Omega’s Master Chronometers, and two from Rolex’s stringent +/-2. All regulation is done in-house, too. Bremont’s own performance benchmark is famously the Martin-Baker ejector seat test, which it says ENG300 has been subjected to – and passed.

They also added a series of high-end finishes, pushing it well beyond K1’s modest aesthetic and giving it a distinct Bremont look. Both the partially skeletonized tungsten rotor and balance bridge have been redesigned to reflect something of The Wing’s swooping façade, and the movement has a handsome circular stripe finish, which, with tongue in cheek, Nick refers to as the Henley Stripe – and why not. When ENG300 appears in core collection pieces some time next year, all of those details are expected to remain.

The nuances of IP transfer aren’t easy to grasp or quantify, but Bremont says 80 percent of the movement by weight has been customized and that the IP for ENG300 now lies with them. Perhaps tellingly, THE+ says admiringly that it sees ENG300 as a different movement to K1, and not just a modification. It says there are 3,500 knowledge steps in creating a base calibre from scratch and that Bremont’s process of absorbing the know-how required to manufacture a movement is almost complete. Some Swiss are for sharing.

Maker's Mark

The next question is of what Bremont is actually manufacturing. In short, five key components – the base plate and the barrel, balance, automatic, and wheel bridges. Lovingly and loveably, the barrel bridge carries the engraving “Made in England.” Everything beyond that, from screws to the silicon escapement and the hairspring, is made by a network of undisclosed third parties. As per industry norms, supplier networks are deemed part of their IP.

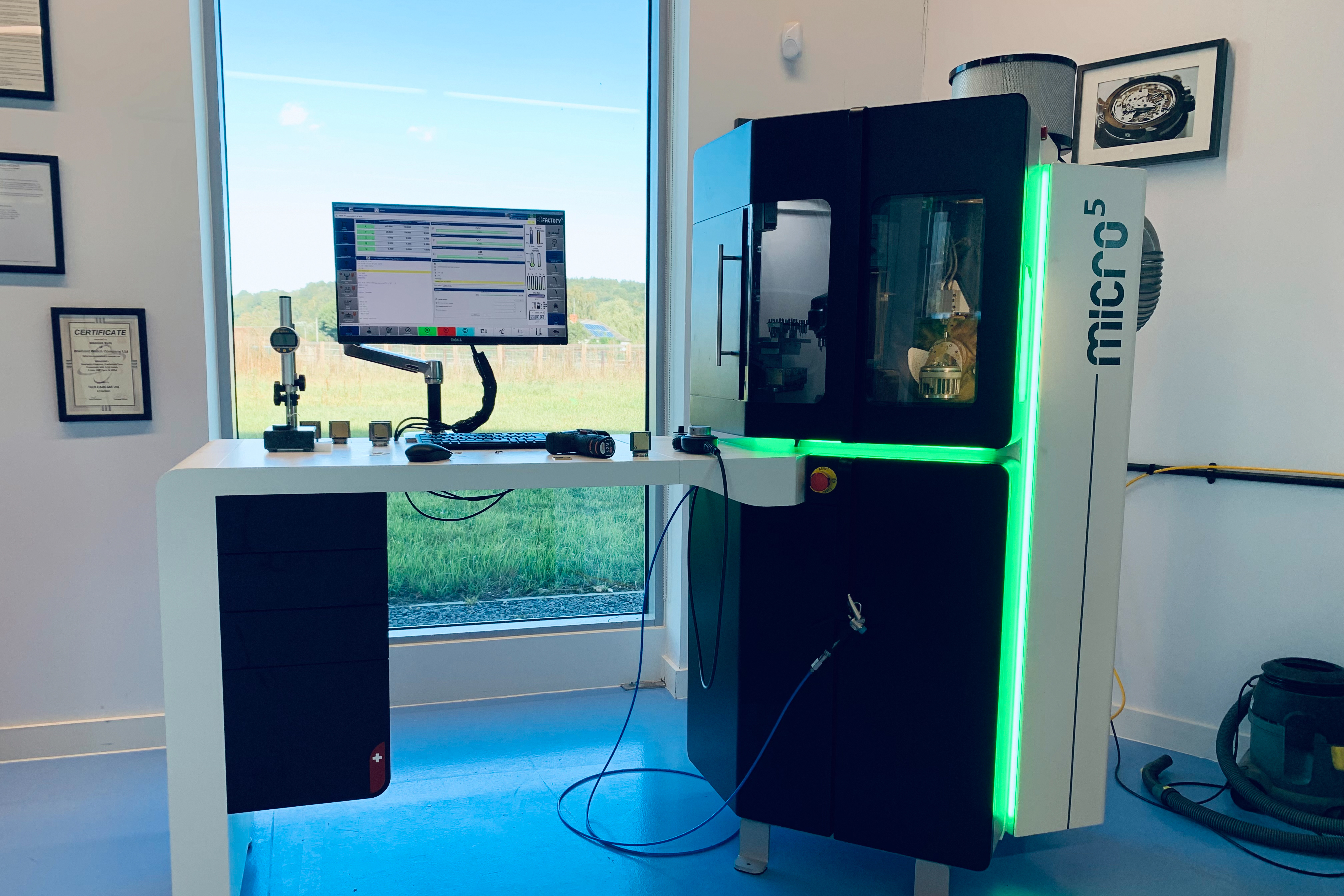

At the north-east end of The Wing is The Micro Hub, a noisy machining room with floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the Oxfordshire countryside and a nearby polo field. It’s modestly sized, at least by the standards of the established Swiss manufacturers, but still houses at least half a dozen machines worth millions of dollars that can produce case and movement parts to, say Bremont, within their tolerance of three microns. I’ve not visited Bremont’s Ruscombe site, but they say there are further CNC machines there, too.

The newest of those in The Micro Hub is a five-axis precision milling machine. It has a name, but Bremont considers it part of its IP, too, and so I’m asked not to mention it. Suffice to say that despite being little bigger than a domestic fridge, it carries a seven-figure price tag. It pumps out parts significantly faster than its larger predecessors, thanks to a drill, I’m told, that can spin at a lightning 60,000 rpm, 50 percent faster than a conventional CNC milling machine. Like a particularly proud father, Nick’s face lights up talking about it. He must have seen this umpteen times already, but he whips out his phone and starts filming. Boyhood dreams still being realized.

On a table alongside it, there’s a pile of plates, 30, 40 of them, all with cut-outs of the ENG300 components Bremont is manufacturing. Anderson, the aforementioned engineer and one of Bremont’s top minds, spent a week programming the machine with its 200,000 lines of code (I saw the file, like an Excel nightmare) and he assures me the pile is around a day’s production. A second machine is due for delivery within weeks, he tells me.

ADVERTISEMENT

Assembly Instructions

Continuing a spirit of openness, I’m told these parts are shipped to Switzerland to be plated. There’s still no facility in the UK that can perform that part of the watchmaking process in the volumes and at the quality Bremont is looking for, but in typical Bremont style, there’s hope in the air that one day there will be. Other British brands would have to join the movement first, they concede.

Back in Henley, some, but not yet all of ENG300’s parts go through T0, the sub-assembly phase. Some processes remain outside the UK. I’m introduced to another contraption, barely larger than a sewing machine, that inserts rubies into the plates.

Two paces away is Michael Bellamy, who designed and oversaw the set-up of The Wing’s workshops. I ask him for his thoughts on ENG300 and he can barely conceal his enthusiasm for its architecture. One detail he shares with me is that it has just three types of screw, where most calibres have up to nine. It’s this kind of design efficiency that helps keep costs down, accelerate the assembly process, and lighten the load of servicing further down the line. Beauty in simplicity.

Also on show is a surface-finishing machine; perhaps 20 workbenches with technicians busy assembling movements and watches; and a quality control lab manned at the time by three strict-looking, loupe-wearing individuals. If the space looks unfinished, it’s because there’s room for more bodies – Bremont has built with expansion in mind, and expects it to come.

The aim for 2022, says Bremont, is that this production line will produce 5,000 movements a year, with further investment beyond to increase capacity further still. These will replace the outsourced calibres powering half of the 10,000 watches they say they’re currently producing every year. It’s hard to see where that extra level of capacity might come from, until Reynolds tells me that when they built The Wing they laid the groundwork for an adjacent extension. Smart. For now, they have no plans to sell either assembled movements, or the IP to ENG300 to other brands.

Testing Times

Photo: The Naked Watchmaker

The final piece in the puzzle is testing. Bremont is sticking with its love of chronometers, but as many will know, COSC won’t certify movements produced outside Switzerland. Already, COSC decline to certify movements in any Bremont watches, although (fun fact) they will test them – the ISO 3159 chronometer rating currently applied to Bremont’s watches is, bizarrely, issued by COSC, just without its own, more recognisable chronometer certificate.

As ENG300 is as British as it is, COSC won’t touch it. And as there’s no UK testing institute, Bremont says it’s left to self-certify (it works for Patek – the quip is mine).

To do this, it’s kitting out a self-contained testing lab on-site. Only one of the three temperature-controlled fridges where the 16-day test will take place was installed at the time of my visit, but with further equipment on order, Bremont is confident it will be able to introduce what it’s calling the “H1 Timing Standard” sometime next year into its core collection.

The base standard is still ISO 3159, but H1 will go further than COSC by testing the complete movement, with its automatic bridge and rotor already assembled. Further down the line, plans are to expand on the standard, but again, for another day.

ADVERTISEMENT

In-House Or Not In-House?

The watch community is slowly moving away from an obsession with the term “in-house.” Its parameters are so poorly defined and so open to abuse – by both brands and commentators – and as those of us on the outside have come to learn, no one has absolute control over every single aspect of a mechanical watch, not even the biggest of the big (Rolex). Although when it comes to watchmaking nomenclature, at some point nuance has to take a back seat: Bremont is simply referring to ENG300 as a “Bremont manufactured movement.”

In summary, then, Bremont’s story is thus: The ENG300 calibre is a re-engineered and upgraded version of K1, a base calibre designed by the Swiss company THE+. Bremont has bought the rights in perpetuity to use THE+’s IP, the whole kit and caboodle. ENG300 is a largely customized version of K1 and the upgrades were developed by a Bremont team. The movement contains five core components made at the Bremont Manufacturing and Technology Centre, namely the base plate and four bridges, and together, these make up 55 percent of the movement’s weight. In all, 80 percent of the movement’s weight is accounted for by parts Bremont has customized. As the transition of knowledge from THE+ to Bremont continues, even the sub-assembly will one day take place at the Centre. For now, they’re comfortable saying 100 percent of the movement (with a few T0 pre-assembled parts) is already assembled at the Centre, and that 100 percent of the regulation happens there, too.

The Macro View

Stepping away from the vast amount of detail (there’s much, much more) and instead taking a macro, but subjective view, Bremont’s is an immense achievement. ENG300 may be unexpected and it may not be entirely British or entirely Bremont’s, but it is the first and most British – and most Bremont – industrially produced movement of my lifetime, which began in the 1970s, not long after Smiths closed down the last comparable operation.

There’s no escaping the fact that Bremont will come under greater scrutiny on launching ENG300 than its Swiss peers might expect in a similar scenario. The Wright Flyer debacle of 2014 looms large and the company may never win back some of those it lost when the BWC/01 calibre was revealed not to be theirs, but La Joux-Perret’s. But I suspect they won’t be Bremont’s loss. The company deserves great credit for peeling back the layers this time – as perhaps it had to.

I’ve always suspected there’s more to it than that, though. Right from the get-go, 15-odd years back, Nick and Giles English were uncommonly explicit in stating their movement-making ambitions, and their greater vision to reverse decades of decline in not just British watchmaking, but British manufacturing.

Some would say that was noble, brave even, and an awful lot for two novice watch brand owners to take on. Others, particularly here in the UK, would have felt it was over-reaching. The stereotype of the pompous Brit who takes a dim view of public displays of confidence is, for better or worse, still entirely warranted.

Indeed, while the international reception will matter to the company, it knows it has a heck of a job on its hands just to convince its British watchmaking contemporaries of its advances, many of whom have made little attempt to hide their skepticism to now. It’s a footnote to the story, but the recently formed Alliance of British Watch and Clock Makers already has 60 members. Bremont, Britain’s largest luxury watch company by turnover, is not one of them. Speaking as a neutral, I hope that changes.

As a side note and by pure coincidence, Peter Speake, formerly of Speake-Marin, was at The Wing at the same time as me, dismantling, studying, and photographing ENG300 for his excellent educational website The Naked Watchmaker, which he runs with Daniela Marin. We discussed the movement for half an hour, without any Bremont faces in the room, and while he was adamant to remain impartial, it was clear he was impressed. By my count, the impressions of one of the most talented watchmakers of his generation means something.

Photo: The Naked Watchmaker

It’s been a labor, of love I suppose, putting this story together, but that is as nothing compared to the journey Bremont has been on to get to this point. I’ve followed this story for most of my professional life, and having walked the corridors and workshops of The Wing twice now, I’m left to conclude that ENG300 is a huge and hugely impressive step for Bremont – and British watchmaking. But it’s not the end game, and nor is Bremont saying it is. Instead, it’s the next chapter in what is becoming a story of many volumes. More will follow, I’m sure. And I’m looking forward to reading them.

Shop this story

The HODINKEE Shop is an Authorized Retailer of Bremont watches; explore our collection here.

Top Discussions

Introducing TAG Heuer Refreshes The Aquaracer Professional 300

Auctions Sylvester Stallone's Patek Philippe Grandmaster Chime Leads New York Auction Week

Introducing Oris Turns The Divers Sixty-Five All-Black For Its 2024 Hölstein Edition